Modeling is all about communication. The UML already gives you all the

tools you need to visualize, specify, construct, and document the artifacts of

a wide range of software-intensive systems. However, you might find

circumstances in which you'll want to bend or extend the UML.

Notes are the mechanism provided by the UML to let you capture

arbitrary comments and constraints to help illuminate the models you've

created. Notes may represent artifacts that play an important role in the

software development life cycle, such as requirements, or they may simply

represent free-form observations, reviews, or explanations.

Stereotypes, tagged values, and constraints are the mechanisms provided

by the UML to let you add new building blocks, create new properties, and

specify new semantics. For example, if you are modeling a network, you might

want to have symbols for routers and hubs; you can use stereotyped nodes to

make these things appear as primitive building blocks. Similarly, if you are part

of your project's release team, responsible for assembling, testing, and then

deploying releases, you might want to keep track of the version number and test

results for each major subsystem. You can use tagged values to add this

information to your models. Finally, if you are modeling hard real time systems,

you might want to adorn your models with information about time budgets and

deadlines; you can use constraints to capture these timing requirements.

The UML provides a textual

representation for stereotypes, tagged values, and constraints. Stereotypes

also let you introduce new graphical symbols so that you can provide visual

cues to your models that speak the language of your domain and your development

culture.

Notes

A note that renders a comment has no semantic impact, meaning that its contents

do not alter the meaning of the model to which it is attached. This is why

notes are used to specify things like requirements, observations, reviews, and

explanations, in addition to rendering constraints. A note may contain any

combination of text or graphics as shown in the below figure:

Other Adornments

Adornments are textual or graphical items that are added to an

element's basic notation and are used to visualize details from the element's

specification. For example, the basic notation for an association is a line,

but this may be adorned with such details as the role and multiplicity of each end.

In using the UML, the general rule to follow is this: Start with the basic

notation for each element and then add other adornments only as they are

necessary to convey specific information that is important to your model.

Consider the below example:

Stereotypes

The UML provides a language for structural things, behavioral things,

grouping things, and annotational things. These four basic kinds of things

address the overwhelming majority of the systems you'll need to model. However,

sometimes you'll want to introduce new things that speak the vocabulary of your

domain and look like primitive building blocks.

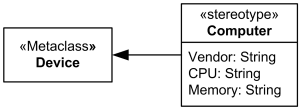

When you stereotype an element such as a node or a class, you are in

effect extending the UML by creating a new building block just like an existing

one but with its own special properties (each stereotype may provide its own

set of tagged values), semantics (each stereotype may provide its own constraints),

and notation (each stereotype may provide its own icon).

In its simplest form, a stereotype is rendered as a name enclosed by

guillemets (for example, <<name>>) and placed above the name of

another element. As a visual cue, you may define an icon for the stereotype and

render that icon to the right of the name (if you are using the basic notation

for the element) or use that icon as the basic symbol for the stereotyped item.

All three of these approaches are illustrated in the below figure:

Tagged Values

Everything in the UML has its own set of properties: classes have

names, attributes, and operations; associations have names and two or more ends

(each with its own properties); and so on. With stereotypes, you can add new

things to the UML; with tagged values, you can add new properties.

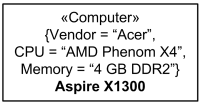

A tagged value is not the same as a class attribute. Rather, you can

think of a tagged value as metadata because its value applies to the element

itself, not its instances. For example, as the below figure shows, you might

want to specify the number of processors installed on each kind of node in a deployment

diagram, or you might want to require that every component be stereotyped as a library

if it is intended to be deployed on a

client or a server.

In its simplest form, a tagged value is rendered as a string enclosed

by brackets and placed below the name of another element. That string includes

a name (the tag), a separator (the symbol =), and a value (of the tag).

Constraints

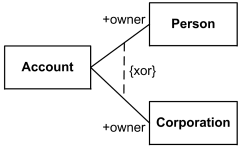

With constraints, you can add new semantics or change existing rules. A

constraint specifies conditions that must be held true for the model to be

well-formed. For example, as below figure shows, you might want to specify

that, across a given association, communication is encrypted. Similarly, you

might want to specify that among a set of associations, only one is manifest at

a time.

A constraint is rendered as a

string enclosed by brackets and placed near the associated element.

Common Modeling Techniques

Modeling Comments

The most common purpose for which you'll use notes is to write down

free-form observations, reviews, or explanations.

To model a comment,

- Put your comment as text in a note and place it adjacent to the element to which it refers. You can show a more explicit relationship by connecting a note to its elements using a dependency relationship.

- Remember that you can hide or make visible the elements of your model as you see fit.

- If your comment is lengthy or involves something richer than plain text, consider putting your comment in an external document and linking or embedding that document in a note attached to your model.

- As your model evolves, keep those comments that record significant decisions that cannot be inferred from the model itself, and unless they are of historic interest discard the others.

Consider the below example:

Modeling New Building Blocks

To model new building blocks,

- Make sure there's not already a way to express what you want by using basic UML.

- If you're convinced there's no other way to express these semantics, identify the primitive thing in the UML that's most like what you want to model (for example, class, interface, component, node, association, and so on) and define a new stereotype for that thing.

- Specify the common properties and semantics that go beyond the basic element being stereotyped by defining a set of tagged values and constraints for the stereotype.

- If you want these stereotype elements to have a distinctive visual cue, define a new icon for the stereotype.

Consider the following example:

Modeling New Properties

To model new properties,

- First, make sure there's not already a way to express what you want by using basic UML.

- If you're convinced there's no other way to express these semantics, add this new property to an individual element or a stereotype.

Below figure shows four subsystems, each of which has been extended to

include its version number and status. In the case of the Billing subsystem,

one other tagged value is shown the person who has currently checked out the

subsystem.

Modeling New Semantics

To model new semantics,

- First, make sure there's not already a way to express what you want by using basic UML.

- If you're convinced there's no other way to express these semantics, write your new semantics as text in a constraint and place it adjacent to the element to which it refers. You can show a more explicit relationship by connecting a constraint to its elements using a dependency relationship.

- If you need to specify your semantics more precisely and formally, write your new semantics using OCL.

For example, below figure models a small part of a corporate human

resources system:

To

assert that a manager must also be a member of the department is something that

cuts across multiple associations and cannot be expressed using simple UML. To

state this invariant, you have to write a constraint that shows the manager as

a subset of the members of the Department, connecting the two associations and

the constraint by a dependency from the subset to the superset.

Notes:

Stereotypes:

Other Examples

Notes:

Stereotypes:

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for your message. We I get back to you soon...